Actually, I was on vacation — a time when one is supposed to be taking a break from work. One of the highlights of my recent trip to the beautiful city of Bolzano was a visit to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, home to the 5,300-year-old mummyMumiemummy known to the world as Ötzi. The “man from the ice” was discovered high in the Ötztal Alps in 1991 by two German mountaineerBergsteiger(in)mountaineers who saw his upper body protrudeherausragenprotruding from the glacierGletscherglacier. I was inspired and moved by what I saw in the museum, and my thoughts quickly turned to work when I learned from the exhibitAusstellungsstückexhibits how the man from the ice is preserved — and what this work means for science and humanity.

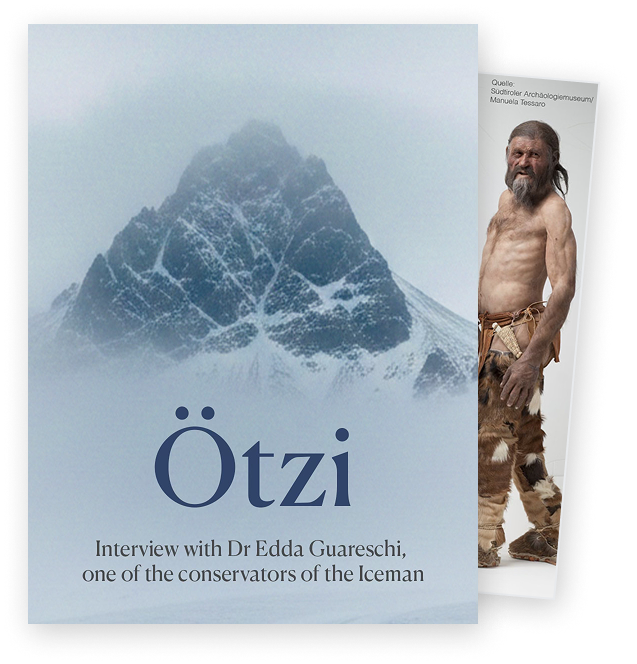

The following is my interview with Edda Guareschi, a forensic pathologist from Parma, Italy, who is working now in an additional role as the paleopathologist and conservator responsible for keeping the mummy preserved. She is one of the few people on the planet who has done this extraordinary job. – Judith Gilbert

Kostenloses Video-Interview

🇬🇧 Dr. Edda Guareschi will den „Mann aus dem Eis“ für nachfolgende Generationen bewahren. Judith Gilbert hat mit ihr über die Bedeutung dieser Arbeit gesprochen.

👉 Jetzt ansehen!

How did you become a forensic pathologist?

I was always attracted to mysterious discoveries and the passing of time and the meaning of humankind and evolution, and the place of humans in the universe. I was always curious about what came before us in the world and what will be after us, because, someday, there will be no “us” anymore; that’s what biology says.

So, I became a medical doctor and worked as a forensic pathologist for 19 years. Then, I moved to Australia with my whole family — my husband and my four cats. I worked there for about ten years, doing research, especially about forensic taphonomy, which means what happens to organisms — humans and nonhuman beings — between death and recoveryhier: Bergungrecovery. Between the death of anything and recovery, you can wait two hours and that’s a criminal case. But if you wait 5,000 years, then it becomes an archeological discovery, like Ötzi.

I’m fascinated by everything that happens over time — trying to understand how we go back to the elements, how we go back to earth, and the cycle renews again all the time. From a strictly physical point of view, we’ve been around forever — because the matterhier: Materiematter that has become us for a few decades was in the universe before we were born, will be in the universe after we’ve decomposesich auflösen, zersetzendecomposed. So, we are basically just one cogZahnrad, Rädchencog in the the big picturedas große Ganzebig picture.

How did you get the job of conserving Ötzi?

I was in Australia, working at a university, specializing in animal and human bones that came from the underwater excavationAusgrabungexcavation of historical shipwreckSchiffswrackshipwrecks, on an academic career path. On LinkedIn, I saw an ad for this position. I thought: “Oh, I’d love to do that, but who’s going to hire someone over 50, who’s been away for that long, who doesn’t have any archeological education, who’s a medical doctor, who has family somewhere else?” I delete sth.etw. löschendeleted the ad. Weeks later, the ad come upauftauchencomes up again. I said: “This is a sign, I’ll apply.” I told myself: “I’m applying, but they’ll never contact me.” But they did.

When I moved back to Italy, I went back to my medical training and started taking care of a human being. Because even though Ötzi is very old — prehistorical, archeological — it’s considered an archeological ecofactÖkofaktecofact. It’s actually a human being. That’s why so many visitors are fascinated, because this museum is not just a museum. This museum, in a way, is a mausoleum, and Ötzi is in his tombGruft, Grabtomb.

What does the conservation of an ice mummy mean?

We attend to sth.sich um etw. kümmernattend to and plan the conservation of the mummy for the future museum, future generations, future researchers. It is a mummy, so it can decayverwesendecay if not preserved in the right environmental conditions, so we ensure that they’re always adhere to sth.etw. wahren, einhaltenadhered to. The temperature in Ötzi’s chamberKammerchamber is minus 6.5 degrees [Celsius], and humidity is between 99.5 and 99.8 percent. It’s dark — UV raysUV-StrahlenUV rays are not good for mummies. We try to replicate sth.etw. nachbildenreplicate the conditions on the glacier where he was found, to replicate his tomb for the last 5,000 years. It’s working.

What do you do to preserve him?

We do photo documentation — once a month or every six weeks — and photogrammetry. We do humidificationBefeuchtunghumidification to keep the mummy in a state of hydration to avoid cracks and drying out. If you have cracks, you have infiltration by bacteria, which could lead to decay. And we do samplingStichprobennahmesampling for microbiology analysis. We sample the air. Every year, there’s a complete disinfection of the cell, not the cell where the mummy resthier: ruhen, liegenrests, but everything around it, to avoid contamination. It’s maximum two or three people at a time going into the cell, two doing any job that needs to be done, and somebody taking the photos. And we make sure that all the equipment around the mummy works, electrical, hydraulic systems, water systems.

And in terms of Ötzi himself?

We take him out and put him onto hospital trayAblagetrays. We have sterile sheethier: Lakensheets, we have all the surgicalchirurgischsurgical equipment, because you have to be very delicatebehutsamdelicate around him. You can’t use just anything. It has to be hospital tools.

The best time, for me, is when we put him back. After the treatment, we say: “OK — that’s all for today. We’ve done what we wanted to do and, now, we can put you to rest again. See you in a month and a half! Take good care of yourself and rest!” We’re taking care of a body; we take him out of his tomb. It feels like: “Sorry, we have to disturb you again. It will be short, but we have to learn from you.”

I’m fascinated by everything that happens over time

What’s your work when you’re not treating him?

The rest of my time at the museum is spent following my ongoing(fort)laufendongoing research from Australia and Italy. Today, it’s so easy to do that remotelyaus der Ferneremotely. I can talk with my former students and colleagues. It’s coordinating research, coordinating intervention on the mummy because, as you can imagine, we have specialists of all sorts: natural scientists, conservation scientists, archeologists, paleoanthropologists — everybody wants to come here and do research. I have to coordinate the conservation of all the samples that have been taken in the past 30 years, close to 9,000 samples, which need to be store sth.etw. lagernstored properly. Making sure that all the freezerGefriermaschine, Tiefkühlerfreezers work. It’s half a desk job and half a dynamic one. It’s all very international here, even if it doesn’t look like that. We’re in a remotehier: abgelegenremote location in the mountains, but we’re not isolated. We’re very connected.

What do you learn from the research?

Ötzi was found in 1991, so a lot of research has already been done. All those samples, they’re not all from the mummy. There are many from the environment: from plants, bacteria, clothes, equipment that the mummy carried or were found close to the recovery site. It’s a snapshotMomentaufnahmesnapshot of life in the Copper AgeKupferzeitCopper Age, from plants to the person, dietErnährung(sweise)diet, migration, equipment, which animals were around, the last meal, pathology and everything else. So, from Ötzi, we can learn how people really lived in this part of Europe more than 5,000 years ago.

Conserving a work of artKunstwerkwork of art such as a Rembrandt must inspire conservators. Does preserving a 5,300-year-old mummy inspire you with a philosophy about life and death?

All the time! What I would like to do is inspire younger generations to think that, even though we’re going through difficult times, in terms of the world now, there is a future, and learning from the past can help us get through these times and look to the future. So, let’s be creative. Let’s think about the new world of tomorrow. Think about what has been done and improved since Ötzi’s times, and what we can do in the next 5,000 years.

OTZI AND THE MUSEUM

The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology is located in a former bank in Bolzano’s historic city center. It has permanent and temporary exhibitions on the archeology of South Tyrol and the southern Alps that are center around sth.sich um etw. drehencentered around Ötzi, the world’s oldest wet mummyFeuchtmumiewet mummy, who can be seen in his chamber, in a controlled, dark and respectful environment.

He was found with his clothing, shoes and tools, all well preserved and uniqueeinzigartig, einmaligunique to the world, as no other organic material from that period has survived. The museum takes visitors through the Alps, through the time of Ötzi’s life and murder, to his discovery and conservation. There are videos of the conservation work and interactive exhibits for adults and children.

South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology

Via Museo 43, Bolzano, Italy

www.iceman.it

Zusammenfassung als Video Interview

Sehen Sie sich das Video "Mummy mia! The doctor who preserves Ötzi" kostenlos an.

Neugierig auf mehr?

Dann nutzen Sie die Möglichkeit und stellen Sie sich Ihr optimales Abo ganz nach Ihren Wünschen zusammen.